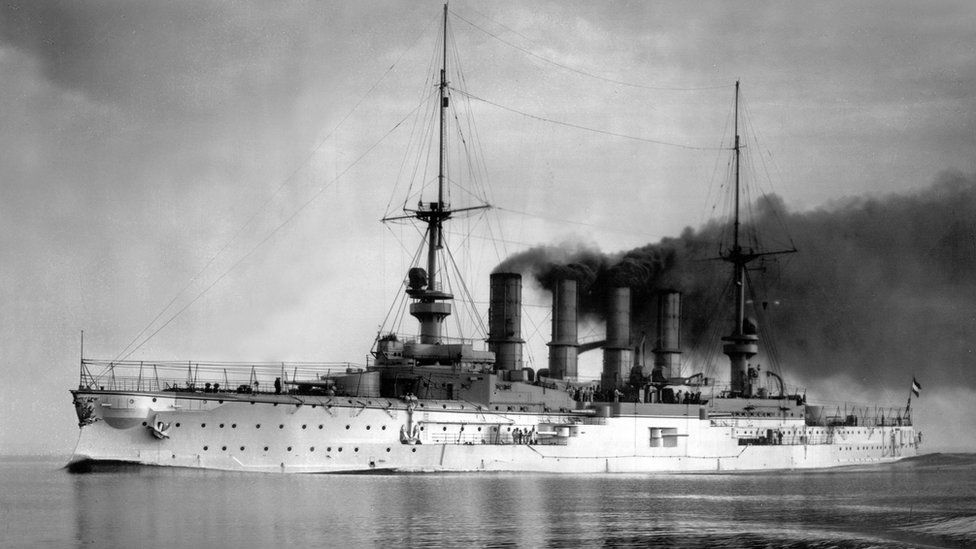

Wreck of the Scharnhorst Located – Announced 5 December 2019

The wreck of Admiral Graf von Spee’s flagship – the powerful German battlecruiser SMS Scharnhorst which was sunk with the loss of all hands off the Falkland Islands on 8 December 1914 – has now been located lying on the seabed, battle scarred but largely intact. The WW1 Battle of the Falklands was significant in that it saw the destruction of Imperial Germany’s only naval squadron operating outside the North Atlantic, avenging the Royal Navy’s earlier defeat at the Battle of Coronel, off Chile, on 1 November 1914. The loss of life in both engagements was considerable. Due care was taken not to disturb the wreck of the Scharnhorst on its discovery and efforts are now being taken to ensure the ship’s protection as a war grave. The search was organised by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust, which hopes eventually to locate the other German ships lost during the Falklands engagement – the Gneisenau, Nurnberg and Leipsig. The Dresden escaped but was hunted down and, under British attack, was scuttled off Chile’s Juan Fernandez Islands in March 2015.

History

In brief, at the outbreak of the war, the German East Asia Squadron under Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee was in the Pacific. Rather than returning to base in Tsingtau in China, where he would be vulnerable to allied attack, von Spee moved towards the Chilean coast to disrupt British and allied shipping there. The Admiralty, under Winston Churchill as First Sea Lord, despatched the ageing pre-Dreadnought battleship, HMS Canopus, to the Falkland Islands under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Christopher (Kit) Cradock to tackle the much more powerful German squadron.

Admiral Cradock sighted the German ships near Coronel, Chile on 1 November 1914, he had command only of HMS Good Hope (his flag ship), Monmouth, Glasgow and the converted liner Otranto; Canopus, slowed by boiler trouble, was 250 miles to the south escorting the British colliers. He was opposed by the two German battle cruisers, SMS Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and the light cruisers Leipsig and Dresden; Nurnberg had been despatched north to investigate suspect shipping. The British ships were outmanouvred and outgunned. Good Hope and Monmouth were sunk with the loss of 1,600 souls, including Kit Cradock; Glasgow made it back to the Falkland Islands with Canopus and Otranto.

The Battle of Coronel was the first major defeat of the Royal Navy for over a hundred years. The Falkland Islands were promptly reinforced by two battle cruisers – HMS Invincible and Inflexible – with the cruisers Bristol, Carnavon, Cornwall and Kent which arrived in Stanley under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee on 7 December 1914.

The German ships had expended much of their coal and ammunition stocks at Coronel. Von Spee therefore decided to raid the Falkland Islands to destroy its wireless communications and to obtain vital supplies of coal before returning to Germany. He had no idea that a British squadron had already arrived and mistook the columns of smoke from the British ships getting up steam for the burning of coal stocks. When Gneisenau and Nurnberg came under fire from Canopus,von Spee first sought to outrun the British ships but then turned to give battle when it became clear that he was opposed by two RN battle cruisers of greater speed and armament.

The Battle of the Falklands saw the almost total destruction of the outnumbered German squadron, with the sinking of the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Nurnberg and Leipsig; only Dresden got away. Over 2,000 German sailors were lost including von Spee and his two sons. Only 200 or so sailors were rescued.

The Battle of the Falklands has been commemorated in Stanley on 8 December as Battle Day ever since – and more recently by an annual ceremony at the Cenotaph in Whitehall organised by the Falkland Islands Association (FIA). On the centenary of the battle in 2014, a special ceremony was held in Christ Church Cathedral in Stanley which members of the von Spee and Cradock families attended. The FIA organised a similar but smaller service at the Royal Naval church of St Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square.

The Search

The idea of searching for the German navy ships sunk in the Battle of the Falklands in 1914 was first taken up by Menson Bound, a marine archaeologist and 5th generation Falkland Islander. Memories of the WW1 battle, despite its annual commemoration in the Falkland Islands, were beginning to decline in the UK even in the official UK Government preparations for commemorating the centenary of the First World War.

With the support of the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and the financial backing of a major donor, Mensun Bound organised the first search for the wrecks in 2014-15 using an old RN vessel, the RVS Endeavour. Despite pursuing the search for 104 days, the attempt was unsuccessful. Problems included the awful weather, the use of old technology but more significantly the absence of exact co-ordinates for the wrecks – the heat of battle and cloud cover on the day, which prevented the accurate use of sextants, meant that the recorded site of each ship’s sinking was inaccurate.

The opportunity for a second (but brief) search, using a modern, state of the art, deep ocean search and survey vessel – the Seabed Constructor – came in 2019. The Seabed Constructor was able to survey the seabed to a depth of 6,000 metres with AUVs (autonomous underwater vehicles) and ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) with sophisticated scanning systems and cameras. It could search up to 1,000 sq.km (390 sq.miles) of ocean daily. The Seabed Constructor, launched in 2013 and owned by Swire Seabed, had been contracted, since December 2016, by Ocean Infinity, a British hydrographic survey company based in Houston, Texas. The ship had taken part in the abortive search for Malaysian Airlines flight 370 in 2018. It was then contracted by the Argentine Government to search for the missing Argentine submarine – the ARA San Juan – which it found on 17 November 2018, just over a year following the submarine’s disappearance.

The area of search was a box of about 4,500sq.km of seabed at a slightly different location from the 2014-15 search area. After only three days, the Scharnhorst was discovered 98 nautical miles SE of Stanley lying in 1,610m (5,280ft) of water. It was discovered slightly outside the search box as the survey ship made a turn and very close to a major drop off of the sea bed. The German ship was upright and in relatively good condition, despite substantial battle damage to the bridge; the wooden bow decking, for example, was intact and fairly clear of marine growth. The main forward guns were at maximum elevation with the smaller side-stationed guns horizontal. It was possible to identify the Scharnhorst from its sister ship Gneisenau by comparing its porthole placements.

Nothing was disturbed or taken, apart from photographs and moving images. A simple ceremony of commemoration was held at the site and steps are being taken to declare the site a war grave to save it from the indignity of being plundered (as had happened with the SS Titanic). A DVD of footage taken by a film production company, TVT, throughout both search periods was shown to the von Spee family in Germany who had attended the centenary commemorations in Stanley in 2014. Later, the film was shown to invited audiences in Stanley and London on 4 December plus two public showings in Stanley on 8 December (Battle Day). The film has been made available to the Historic Dockyard museum in Stanley so that it and all accompanying information will be available to the Falkland Islanders and visitors to the Islands. In due course the DVD will go on public sale.

The Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust hope to continue the search for the other warships sunk during the battle but this will depend on funding and the availability of a suitable search vessel.

Photograph Courtesy of the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust